|

| "Winter holidays in the southern states." 1857 / PD LOC |

Groban piped the words, "Chains shall He break for the slave is our brother; And in His name all oppression shall cease."

My mind raced. Had this song I have heard thousands of times from radios and mall loudspeakers, church organs and choir voices, really been a mystery to me the whole time? Where did that line come from? Did it mean what I thought it meant?

In 1847, Placide Cappeau de Roquemaure, a french wine commissionaire 1, composed a short poem for his town's priest. Adolphe Adams, a world-renowned composer of operas set the poem to music and the "Cantique de Noël" was born. The world around the song was one of tumult and strife. Ideas were changing and shifting. The following year, Karl Marx would publish his Communist Manifesto, a treatise on class struggles between, "freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf," and set the world on an alternate course. Cappeau would eventually become an adherent of France's version of socialism. In that light, the third verse of the poem cum carol is striking:

Le Rédempteur a brisé toute entrave:

La terre est libre, et le ciel est ouvert.

Il voit un frère où n'était qu'un esclave,

L'amour unit ceux qu'enchaînait le fer.

Qui lui dira notre reconnaissance,

C'est pour nous tous qu'il naît, qu'il souffre et meurt

The Redeemer has overcome every obstacle:

The Earth is free, and Heaven is open.

He sees a brother where there was only a slave,

Love unites those that iron had chained.

Who will tell Him of our gratitude,

For all of us He is born, He suffers and dies

How much of European socialist thought American Unitarian John Sullivan Dwight was aware is unclear to me at the moment. He was an avid traveler, and more than likely discovered the haunting melody of the "Cantique de Noël" on a trip to Europe. Dwight was a jack-of-all-trades: theologian, social activist, music critic, publisher and composer. His religious sect predisposed him to American liberal ideologies and the Abolition movement in particular, which was gaining increasing momentum through the tumultuous 1850s.

|

| An ad for Dwight's song from The New York Musical Review and Gazette. |

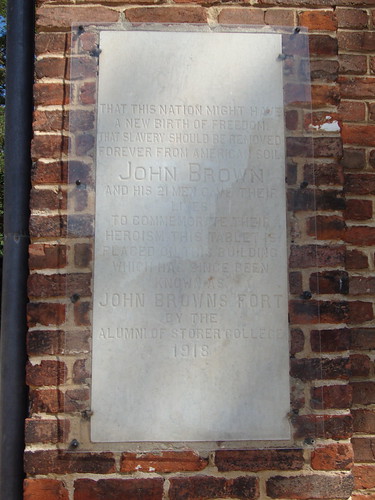

That Christmas of 1859 must have looked bleak. America seemed on the precipice of destruction. Violence and murder had broken out in the streets of a Southern city over the question of slavery. A rising sectional Republican party stood ready to challenge the Democratic establishment. The world was being torn apart and need of redemption.

In Dwight's translation, the song's third verse took on a new meaning. Now not simply a tale of European class strife, the song embodied an American struggle for freedom in the face of systematized tyranny:

Truly He taught us to love one another;

His law is love and His gospel is peace.

Chains shall He break for the slave is our brother;

And in His name all oppression shall cease.

Sweet hymns of joy in grateful chorus raise us,

Let all within us praise His holy name.

In an age when the Bible had been leveraged to both justify slavery and damn it, when human nature was argued to be both predisposed to and above enslavement, when the very humanity of another man was called into question, Dwight's admonition that the, "gospel is peace," was pure and biting. To the Unitarian mind, the Bible inherently stood against the enslavement of another race.

Gone now is Cappeau's reference to suffering and death. In the Unitarian mind, Christ was not a divine being but only a sage teacher. Christ the rabbi, not Christ the mystical savior, sat at the heart of Dwight's view of the world. In his version of the song, then, Christ is not redeemer through blood sacrifice. Instead he is the ultimate Abolitionist by example of the words and actions he took while living.

Living within this song which we hear everyday this time of year lives the lifeblood of the Civil War. Through its lyrics, we are transported back in time (consciously or subconsciously) to an era when the question of American liberty stood in the balance. At Christmas, through this song, we are immediately taken to a world on the edge of either destruction or redemption, of cataclysm or salvation.

My favorite version of the song, however, never mentions slaves or chains, never faces the theological crisis of Christ's divinity. It is instrumental.

| Listen to the Studio 60 version of the song by clicking above. |

At the close of the episode, a group of musicians from New Orleans play a reverent but deeply New Orleans version of "O Holy Night." Played by black hands, in a style grown out of the spiritual tradition, the piece sings in a way that it never had before to my ear and really hasn't since. The pain and heartache, the hope and joy, the future and the past are wrapped in the sound of those brassy notes. As the last tone fades, you smile. The world will go on.

Made wholly possible because of the song itself and the Abolition movement it embodies, there is deep meaning within those notes. They make us hope. They help us see a world beyond suffering and oppression. They let us live.

Merry Christmas from the 1850s.

A time of peace. A time of war.

A time of sorrow. A time of hope.

Because, after all, what time isn't all of those things.

-----

^1 - A wine commissionaire worked for a wine producer, undercutting prices on grapes and pitting vineyard versus vineyard in bitter rivalries for the lowest bids.

^2 - Often this date is listed as 1855, and Dwight's own Journal of Music is listed as the place of publication. Searching each issue for 1854, 1855 and 1866 yields no results for any combination of the lyrics to the song. More than likely he published the song in another publication.