Sorry for drifting a little off course from

the promise of a discussion of universal relevance, but this one seemed important. Tune in next week for some thoughts on universal relevance and race. Now, on to

this week...

-----

I read Louis De Caro's "John Brown the Abolitionist -- A Biographer's Blog" regularly because I deeply respect the work which DeCaro has done in researching Brown, particularly putting him into the context of his religious life. I assigned

"Fire from the Midst of You": A Religious Life of John Brown to the students in my class this semester on Brown, as it is an intriguing look at the abolitionist. But I read DeCaro's blog because I don't agree with him on many of his criticisms of how Brown is interpreted in a modern context. I try to follow a rule of thumb: you need to read those with whom you disagree voraciously, to keep you from growing complacent in your opinions.

DeCaro repeatedly has expressed issues with how the National Park Service (and others) have interpreted Brown's raid and his justification in taking others' lives, most recently

in his post about the Smithsonian's "Time Trial of John Brown," a program which

Jake highlighted last week. DeCaro is critical of the Smithsonian's Susan Evans' statement that, "We don’t want to make out John Brown to be a hero at all...." He continues, stating that, "...like the staff at the National Park Service at Harper’s Ferry, evidently the staff at the Smithsonian Institute’s Museum/Theater have an opinion about Brown."

|

The hat I wore at Harpers Ferry, atop a

period advertisement for a slave raffle. |

My day job is in the NPS. I worked at Harpers Ferry for three years in the living history branch, wearing the clothes of both civilians from 1859 and soldiers from 1862-1864, all the while helping visitors to understand and appreciate the blow for freedom Brown struck in the small Virginia town. You don't work alongside a figure like John Brown, in the places he inhabited, without forming an opinion about the man. To say, "evidently the staff... have an opinion about Brown," is a relative no-brainer.

So what's my opinion on Brown? I think he struck the match for a holy war, a war that was guided by a principle that there is law and there is justice, and the two don't always meet. I think he struck for freedom, using violence to combat a violent system and begin the destruction of the purely evil concept of human chattel slavery. I think that Brown was, to some degree, just. I hate violence, I don't think it is the right answer, but I can understand and appreciate how someone might come to the conclusion that it is necessary. I have never had chains on my wrists, never been dragged along in a coffle, and never seen friends subjected to that treatment. I simply don't know what violence would well up in my soul if placed in the position of a Dangerfield Newby, Shields Green or John Brown.

Here's the clincher, though: my opinion of the justice of Brown's actions matters not one lick. My opinion is not valid in the case of Interpretation. Instead, it comes down to the visitors' opinions of Brown and his raid. The difference between History and Interpretation is a question of dictatorship, muddied by an intersection of language.

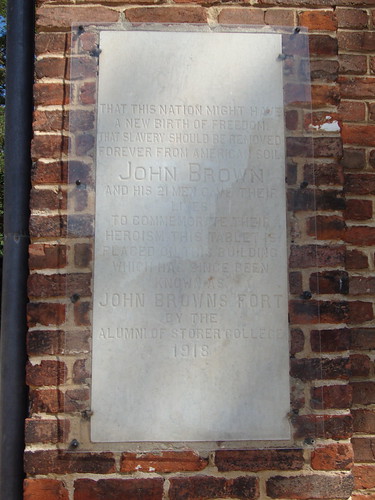

|

Above all else, this is a place to investigate

ideas. / CC by Mike Sheridan |

|

"The chief aim of Interpretation," father of the craft Freeman Tilden intoned, "is not instruction, but provocation." Interpretation is a process by which the individual begins thinking about a place or person or thing. The aim is not learning, but drawing ones' own conclusions. "Information, as such, is not Interpretation," Tilden outlines in another of his principles, "Interpretation is revelation based on information. But they are entirely different things." The outcome of Interpretation is not for a visitor to walk away with one meaning for a place, imparted to all, but to walk away with a personal meaning for that place, developed by themselves. Interpretation represents a democracy of meanings, where only one intellectual vote counts: that of the visitor in their own internal decision of what this place or thing or person means. "Any Interpretation that does not somehow relate what is being displayed or described to something within the personality or experience of the visitor," Tilden warned, "will be sterile."

History, on the other hand, is chiefly instructive. Any historical monograph has a deep seated position, with which it is the author's aim to entice, persuade, goad and sometimes even force the audience to agree. There are right interpretations and wrong interpretations in History, with opinions being as sacrosanct and immovable as the facts and information upon which they are based. There are experts, there to impart a distinct view and interpretation of an event or place or person.

Note that word: interpretation. This is where understandings of the fundamental differences between the two fields begin to break down. The concept of an historical interpretation, or an opinion about what a collection of facts mean in the greater scheme, has little to do with Interpretation as an activity. Capital "I" Interpretation is about eschewing enforcement of specific interpretations on visitors. In short, the difference is as simple as the difference between dictatorship and democracy.

Those are two very loaded words. But they are illustrative. Historical dictatorship only allows one viewpoint. Like Stalin effacing malcontents from photographs or Winston Smith sliding disappeared Ingsoc Party members into a slot in his office's wall, the grand majority of facts left within historical argument are those which support a thesis, either predetermined or crafted from those facts which fit it. Historical argument, to a greater or lesser extent, is a game of stage magic. The proof of something happening comes from not only illustration, but from misdirection as well. But the clincher in this paradigm is that "p" word: proof. Historical dictatorship comes through a distinct use of an

officious tone. Historians impart singular "truths" and sole meanings for events like dictators, with a sense of certitude which often the public rejects. It is a chief reason that academia is disdained by a chunk of the populace as the embodiment of

arrogance: the continual

hubris of thinking "we know better than you."

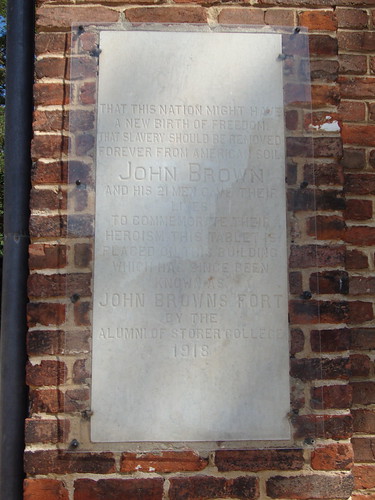

|

Was Brown a terrorist? It is a valid question.

And the answer all hinges on whose eyes

you try to see him through. / CC by Stephanie |

The flip side of the coin, the Interpretive democracy, offers up all the contradictions. It offers up disparate parts and multiple perspectives. It presents the evidence for a point, against a point and everywhere in between. It not only leaves the malcontents in the photos and the documents unburned, but demands that you try seeing the world from their perspectives as well. In this world, you try to see the world from the perspective, through the eyes, of a Virginia planter looking northward at the threat of more Harpers Ferrys. You look through the eyes of the Washington politician just hoping to live out your term in office without provoking a war between white and black, or state and state. You look through the eyes of Brown too, and try to see his perception of justice.

Most importantly, you don't offer a meaning. You offer the ideas of the past, the multiple perspectives, but then refrain from judgement. This is not because judgements should not be made. Everyone does have a right to judge the past and find meaning in its folds. No, this is to make sure that judgement is never imposed. Each visitor's judgement is sacred, is sovriegn. They vote on their personal meanings in a democracy of one.

I gave programs in Harpers Ferry this past summer, focusing on the moral quandary of John Brown's Raid. In it figured Dangerfield Newby, free slave and avenging husband, killed while desperately grasping for his family's freedom. In it too figured Thomas Boerly, Irish immigrant and protective husband, killed while doggedly trying to repel raiders from his town and his family's doorstep. Who was right? I never said. When you wear that badge, when you wear that hat, your word is law. Those two symbols are too powerful to make a judgement. Instead, I left it to the audience. If they walked away believing John Brown a saint, I did my job. If they walked away thinking John Brown a terrorist, I did my job. If they walked away thinking

anything about John Brown, I did my job.

A friend of mine (now lost to us) wrote in his journal in 2002:

A story - that has to be the holy word. More than a plot or narrative - it has to offer real opportunities to meanings. Not a TV movie. A story has to weigh more. Be able to crack open at the details.

The formula now is really quite simple. Make people care about a character, place, - something. Then understate the obvious. First let them feel.

Letting people feel these places and draw their own conclusions is the ultimate democracy of history. Letting them question and prod from any angle, and most importantly not telling them they are wrong for a belief based in the place's story, is the ultimate opportunity to connect with a place. That's Interpretation.