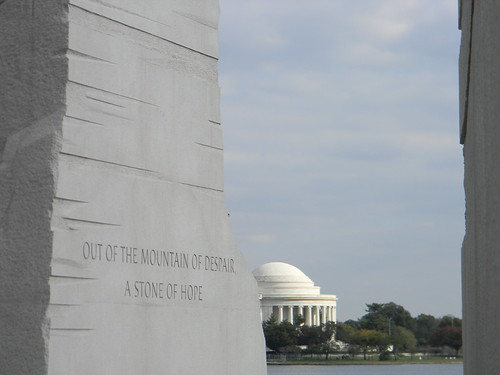

| From darkness to light. |

Physically, I walked from the Arlington Cemetery Metro Station across Memorial Bridge, then continued down the National Mall to 4th Street, where I witnessed one of the most peculiar regularly scheduled celebrations that Americans observe: the Inauguration of the President.

But along the way, I met the past alive on the landscape. I watched the sky turn from murky black into hopeful, bright pink and orange sitting alongside the savior of the nation. Lincoln and I watched as the early light of sunrise silhouetted the brightly-lit Washington Monument. We watched the dark melt to light, the chaos and unknown melt into bright order.

The two of us sat on the steps of his Memorial and watched his nation. It's a nation he could have never dreamt of and yet one he saw clearly in his greatest hopes. The man in the White House, Lincoln's house, looks like the slaves that Lincoln helped begin to truly free 150 years ago. His skin is the same dusky hue.

Meeting him on the street in 1858 in Washington, you might have assumed he was some man's property.

But meeting him on the street in 2013, you can only assume he truly is his own man, as are we all, and you would instantly know he is the leader of a vibrant and constantly evolving nation.

The man who lives in the White House looks like the slaves did, in this, the Sesquicentennial of their freedom. And Lincoln smiled down from his seat in his Memorial. A land he could never imagine, and dreamt of every night.

|

| Reflecting on war and meaning. |

I peered a the line that marks old from new on the side of Washington's Monument, the scar of a war and the resolve of a people to do honor to their father. And next door I saw the foundation of a new museum dedicated to the race of people that that father held in bondage: irony is telling.

Then I stepped onto The Mall and democracy came alive. Walking down the long muddy front yard of the nation, flanking both sides of the path, a chorus of, "good morning." Over and over. High-fives and handshakes from strangers. This wasn't a strange place. We were being welcomed home.

And then Senator Schumer began to speak. His words were brief, but powerful. They were solid and heavy, they soared like a light dove on the wing.

They were interpretive.

I've placed a full transcript of Chuck's short address in the new 'Sources and Miscellaneous' tab above. They're worth another read if you heard them, and a first read if you didn't.

Chuck spoke like a seasoned interpreter, carving meaning where none existed before for the stunned audience. The black smudge on the skyline, the fuzzy statue at the crest of the Capitol Dome, became something more.

|

| Welcome home. |

In fewer than 5 minutes, the moment had passed. The celebration continued. But Charles Schumer had taken those moments and used them to transform that meaningless statue, to ignite it like a torch in the soul. That's what interpretation is: we, at our best, take the meaningless and turn it into a beacon to guide the heart and comfort the mind. And bronze became lighthouse Monday morning.

"So," Schumer concluded, "it is a good moment to gaze upward and behold the statue of freedom at the top of the Capitol Dome." And what could the statue provide? "It is a good moment to gain strength and courage and humility from those who were determined to complete the half-finished dome."

Strength, courage, humility, drawn from a simple hunk of bronze atop a cast-iron dome masquerading as marble. And yet, there it stands: strength, courage, humility... and Lincoln's wildest dreams fulfilled.