|

| The Stone of Hope: a kind King |

"You need to get your picture taken, girl," one asks the other.

"Why?" she responds, "I've got plenty of pictures."

"To prove you were here," the first woman responds.

That hit me. This place was special and meaningful, far above the power of even its creators to see. The very act of visiting the huge stone monolith needed to be documented and shared with those at home, like evidence of a hajj to a sacred spot where all yearn to stand.

During our visit we walked past an older couple, old enough to have been dating as King embarked on his final campaign for the sanitation workers of Memphis in '68. The woman pushed the gentleman in a wheelchair, both looking up reverently at King's face as they moved forward. His black hand rested on her white skin perched gently above his shoulder.

|

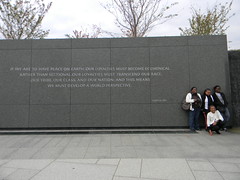

| A Family and a King quote |

Along the walls behind King, next to quotes about strength and weakness, about war and peace, about violence and justice, families posed to have their photos taken. Others studied the quotes, pondering for long minutes. Along the pathways, lining every inch of curb, groups sat. They were talking.

Stepping into the Lincoln Memorial is often like a walking into a wall of silence. Crossing the plain of the columns on the east front, the air becomes deathly still in reverence to Lincoln's gaze. But walking onto the plaza surrounding King's feet, a low murmur permeates the scene. It is not irreverent. It is simply people being people. Some I overheard discussing King or their lives or the meaning of the place. Others were planning where to eat dinner or hashing out the best route to their next stop. Some were simply taking a moment to sit a breathe, looking across the tidal basin toward the white dome in the distance. But everyone was using the park, not simply soaking it up as a static visual landscape to be consumed. They were active participants in the place.

Walking around the site, my girlfriend Jess noticed something I missed. "Look at all the disposable cameras," she remarked. She was right. There were so many people not with the latest Nikon or Kodak camera slung around their neck, or an iPhone snapping quick shots of King, but with $5 and $10 disposable film cameras. "Those people aren't here 'cause they want to be," Jess mused, "they're here because they need to be. They saved money for the Greyhound down from where ever because they had to see this. It is a need, not a want."

|

| Not Diversity: Only A Manifestation of America |

But at the King memorial, it doesn't feel artificial. It doesn't feel like I'm alone and different. It doesn't feel like anyone is missing. The only thing surrounding me at the King Memorial this past Saturday was what defines America: ordinary people of every stripe and any color.

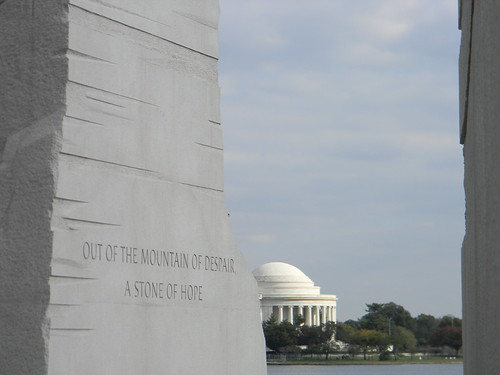

The most amazing thing, though, is looking beyond King's gaze. Across the tidal basin lies the Jefferson Memorial. On one side of the water stands the author of the immortal, "promissory note," that men are entitled to, "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." On the other side, just a stone's throw and two centuries away, stands the man who made it his life's goal to see that the, "promissory note," would be cashed for a race of men yearning to breathe free.

|

| "We hold these truths to be self-evident..." |

No comments:

Post a Comment