|

| What happens when you don't die clutching a photo of your kids? / PD LOC |

But who's buried next to him?

We know Amos Humiston, but the man next to him is a mystery. To the New York father's right is another man, another soldier who fought and died for the flag, for the nation, for the freedom of four million. He has a last name, partial information, a unit and not much else.

And searching finds relatively little on him. "Chamburg" of the 134th New York is a relative mystery. There are no Federal soldiers named Chamburg listed in the rolls of the Army of the Potomac. Not a one.

The 134th New York Infantry did have a Private Jesse P. Chamberlin who was killed at Gettysburg. The man buried next to the famous Gettysburg unknown is more than likely Private Chamberlin.

But who was Chamberlin, then?

In 1860, a Schenectady County census enumerator recorded the details of Jesse P. Chamberlain and his family. The 40-year-old laborer had a young 28-year-old wife, Hulda. Safe in their home in Duanesburg were twin 4-year-old boys, Arthur and Oscar, and a new 2-year-old daughter named Cornelia. And Jesse Chamberlain left them all behind when he enlisted in the 134th New York in August of 1862.

Moved toward the front just after the battle at Sharpsburg, stood in reserve at Fredericksburg and suffered only eight wounded men at Chancellorsville, Gettysburg would be their true baptism by fire.

News of the battle at Gettysburg began trickling into the Schenectady Evening Star and Times in the first few days after the battle. On July 9th the editor ran an excerpt from a letter written in the frantic moments after the battle. But the news was piecemeal. The friends and family of the 134th New York Infantry waited, fearing.

The next day, more casualties. More fear. Henry Teller wrote to the paper that the, "regiment went into the fight about three hundred strong, and came out with twenty-seven men and five officers." That simple sentence must have ricocheted in the minds of the men and women of Schenectady County. Did Hulda Chamberlain hug Arthur and Oscar tight to her side as she heard the news? Did she hope as she tucked Cornelia in to her bed that her beloved father was alright?

July 11th brought glad tidings. Lieutenant Colonel Allan H. Jackson had survived the harrowing first day of the battle, ferreted away in the town as rebels swarmed through the streets and, under cover of darkness, "by running through the rebel pickets got back to our army." It seemed anyone might have survived.

|

| What does gripping horror in the newspaper do to the folks back home still waiting? How many times do they put their husband's face on Jake Trask's body? |

Had Hulda figured it out yet? Did she know? Or did she still hope against hopes that her husband would return to his two sons and daughter?

All hope died on July 22nd, as a complete list of killed, wounded and missing was passed along to Schenectady by Colonel Jackson. There, in hard black-and-white, the only man listed as outright killed in Company H: Private Jesse P. Chamberlain.

All-told, 37 men were killed in the fighting on July 1st, Jesse Chamberlain among them. Arthur and Oscar would never see their father again. Cornelia more than likely wouldn't remember him at all. Another father among thousands buried beneath Pennsylvania's soil.

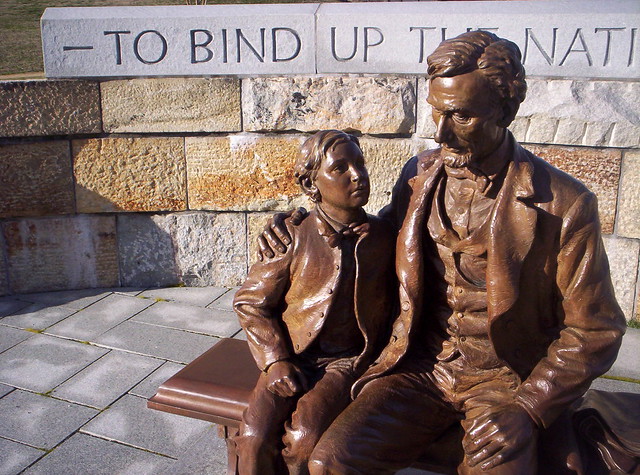

But unlike Humiston, whose grave eventually was marked properly and is venerated by thousands who come to meet the soldier who J. Francis Bourns made into an icon, Jesse Chamberlain gets no mourners. As visitors stand at Humiston's grave, do they ever wonder who "Chamburg" is?

I never did before. I'm a bit ashamed of that. How could I stand there and not obsess over who was buried in that grave? But now I know I should kneel down at Jesse's side too and mourn along with Arthur, Oscar and Cornelia. I'll wipe away Hulda's tears 150 years too late. Then I'll move on to the next grave and do the same.

After all, that man died for freedom too. Just like Amos Humiston.

And Jesse Chamberlain.