|

| The Georgetown Pike Bridge, near where the 87th Pennsylvania bathed in their own blood. / PD LOC |

Gathered around their table were his brothers and sister. David and Louisa were a few years older than the 19-year-old Elias. Robert and Jacob were his younger brothers, 16 and 14-years-old, who likely helped out around the shop when they weren't studying.

When the war began, Elias leapt to the call. Literally in war's first moments, immediately after Lincoln put out the call for volunteers, Elias signed his name on a form and marched to Harrisburg to join the troops who would end the rebellion swiftly and decisively.

In 90 days, he was discharged and America was shown this might not be a quick war.

So Elias joined the army again.

While he was gone, most of Elias father's market for carriages had likely dried up. Did the family need that money now? Was it helping make up for the cash that no longer flowed from wealthy, carriage-buying slaveholders in the Shenandoah Valley? Elias, to some extent, was helping to destroy his family's livelihood while he marched in the United States army. The slave wealth of the South paid for the fancy carriages he built in a previous lifetime.

By July of 1864, the 87th Pennsylvania had seen blood. And as rebels again charged toward the border, they were detailed from Petersburg's defenses to head toward Washington City and protect it from the oncoming tide of Early's raid on the Capital.

Gettysburg knew just moments after the fighting stopped that a battle had happened at Frederick, Maryland. But who was there? Were they dead?

Did Mary Sheads frantically search the columns of the Compiler on the 11th or the Adams Sentinel on the 12th, looking for Elias' name?

Or by now had he been gone so long, been threatened so many times in her imagination, that it was a mundane slow finger rolling down those columns? After seeing the suffering of last summer in her own streets, was her search now simply for the inevitable, not the dreaded? Was war normal by this its fourth long, hot summer?

In a field south of Frederick, Elias Sheads Jr. suffered the inevitable. The 87th was standing astride the Thomas Farm, Georgians charging headlong into their lines. A fragment of shell sailed through the air and buried itself into Elias' shins. Both his feet were shattered, blown to pieces, sheared clean off.

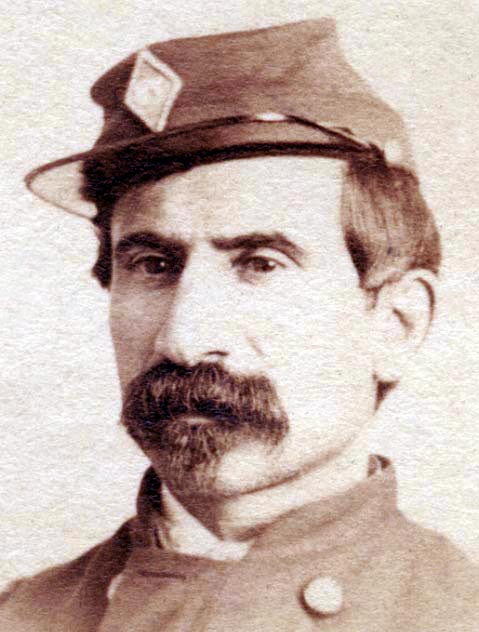

|

| Elias Sheads Jr.'s final trip home ended here. / Find-A-Grave |

He had worked wood with his father, driven pins and nails, laid down leaf springs and set axles. He had built the wagons which easily rolled between Gettysburg and Frederick before this cruel war. He used to make the world smaller, the distances shorter. He and his father transformed a few days' walk into a few hours' ride. If only he could make that ride, leap into a carriage and just go home.

But he couldn't. Instead, he lay, bloody stumps where his feet used to hold him up as he worked. Just a stone's throw from his father and mother, from David and Louisa and Robert. A stone's throw from safety at home.

His body made that one last trip his conscious mind never could. Elias Sheads Jr. was buried atop Cemetery Hill in Evergreen Cemetery.

As soft earth was moved in Gettysburg, somewhere in the trenches around Petersburg, Elias' little brother Jacob stood in the ranks. The 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry, lately transformed into infantry, was moving back and forth along the line, preparing for fight after fight. Jacob, who went by James, was nearly 18-years-old.

Another of Mary Sheads' boys was just waiting for the inevitable.