|

One of the first tangible signs of Virginia's

secession was the removal of the American

Flag from the Richmond Enquirer's

masthead. |

The early teens of April seem to have been specifically engineered by Ex-governor Wise and some of the members of the Secession convention jonesing for separation of from the Union. A

notice ran in the Alexandria Gazette on April 1st, declaring that on the 16th of that month a, "grand Secession demonstration," would be held in Richmond. Among those signing the notice was Henry Wise. The

Gazette reported that, first news of it came from Norfolk," just a stones throw from Wise's home in Princess Anne County. "Perhaps they think the Convention too slow," the

Gazette presumed, "and wish to hurry them up by a sufficient force here." Wise was massing an army of public opinion in the streets of Richmond.

As Alfred Barbour was making his way to Washington to submit his resignation to the Ordinance Department, Henry Wise was arriving on the floor of the Virginia Secession Convention. He had just the night before put into motion the key players to ensure Virginia's separation from the United States. His trap had been laid. All that was left was to spring it on the commissioners assembled in Richmond.

The second day of secret sessions went relatively uneventfully at first. A motion was brought to the floor to delay any decision on the question of secession until election day in late May. Commissioners argued that the people of the Commonwealth, and not their elected representatives, needed make the momentous decision.

The morning session stretched into the afternoon. Wise must have grown increasingly more impatient knowing the scheme hatching outside the doors of the hall. He had engineered an attack on the Federal Government, in direct opposition to the wishes of the state's ruling authority. He had massed an army of rowdys outside, eager to set, "the course which Virginia should pursue in the present emergency." Wise pounced on the moment, calmly rising to the podium. He had no guns in hand, no outward sign of threat. He spoke to the convention:

"I know the fact, as well as I can know it without being present at either the time or place, that there is a probability that blood will be flowing at Harper's Ferry before night. I know the fact that the harbor of Norfolk has been obstructed last night by the sinking of vessels. I know the fact that at this moment a force is on its way to Harper's Ferry to prevent the reinforcement of the Federal troops at that point. I am told it is already being reinforced by 1,000 men from the Black Republican ranks. I know the fact that your Governor has ordered reinforcements there to back our own citizens and to protect our lives and our arms. In the midst of a scene like this, when an attempt is made by our troops to capture the navy yard, and seize the Armory at Harper's Ferry, we are here indulging in foolish debates, the only result of which must be delay, and, perhaps, ruin."

The convention descended into bedlam. Even though he did not brandish a horse pistol, the Ex-governor did hold a proverbial gun to the head of the secession convention. Choosing his words carefully, Wise had not entirely lied.

A Governor had commanded militia to Harpers Ferry. Certainly it was the Governor (ex or not) who commanded the loyalty of many both within the chamber and without.

The two delegates from Augusta County immediately expressed dismay at the news that war had been precipitated without their consent. When John Baldwin raised his concerns, Wise fired back snidely that he knew for a fact that men from his Augusta (those under Imboden’s command) were marching on Harpers Ferry at that very moment. “The Augusta troop are acting nobly in this matter.” George Baylor then made it known he stood firm against Wise. “We are told,” he spoke, that, “blood will be shed…. I do not deem it improbable that my own son is among the number. If he is not, certainly, some of the best friends I have are there.” Baylor could not stomach his own son’s blood on his hands. “I am sorry to say, sir, that I cannot approve of it. Yet, this Convention is going to pass it, whether I vote for it or not.”

The convention voted to leave the union. In the nearby counter convention, organized in part by Wise, jubilation reigned. "The Union had received its

blessure mortelle, and no power this side of the Potomac could save it," John Jones recalled in his

Rebel War Clerk's Diary at the Confederate States Capital. Upon the announcement that Virginia was no longer in the United States, cries went up from the throng. Soon thereafter, "President Tyler and Gov. Wise were conducted arm-in-arm, and bare-headed, down the center aisle amid a din of cheers, while every member rose to his feet." Tyler spoke first, giving, "a brief history of all the struggles of our race for freedom, from

Magna Charta [sic] to the present day." The feeble former President, close to death, concluded that, "generations yet unborn would bless those who had the high privilege of being participators in," the secession of Virginia.

Then Ex-governor Wise rose. Wise, "for a quarter of an hour, electrified the assembly by a burst of eloquence, perhaps never surpassed by mortal orator." The crowd hung on every word he spoke. "Affection for kindred, property, and life itself," Wise instructed the crowd, "sink into insignificance in comparison with the overwhelming importance of public duty in such a crisis as this." Wise's actions, what he percieved as his public duty, bordered on treason, not simply against the United States but against his own Commonwealth of Virginia. Wise had forced the hand of the state into seceding. Governor Wise had percipitated war and was getting naught but laud for his actions.

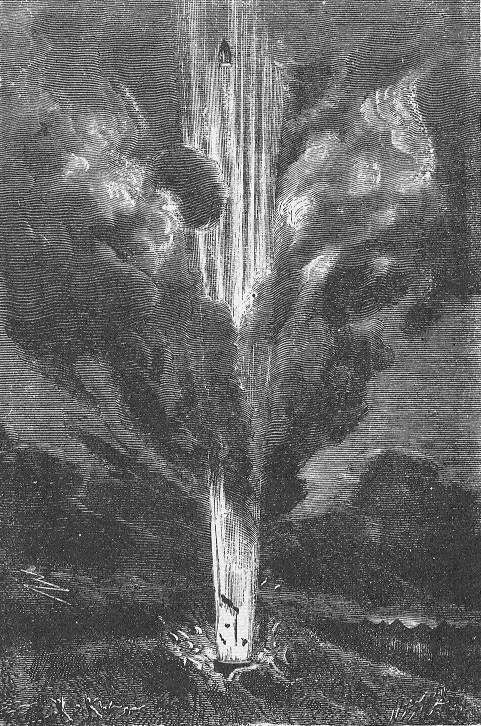

The next day, Alfred Barbour's loose lips at Harpers Ferry tipped off Charles Kingsbury, Harpers Ferry armory's final superintendent, and Roger Jones, commanding the mounted rifles defending the installation. The pair decided to destroy the armory before if fell into enemy hands. War in earnest had come to Virginia.

The moral of this story is simple. Sometimes the things we take for granted, like a few simple sentences from our interpretive programs, are not quite as simple as they seem. Virginia's secession is at once devilishly easy to understand and excruciatingly tough to fathom.

"Virginia seceded from the Union. The Governor sent militia to Harpers Ferry to seize the armory. Roger Jones burned the armory to keep it from falling into enemy hands." The order is wrong, the players are wrong, the concept is wrong. Just a few short trips into the primary sources can unravel even the smallest details of any piece of history. History is a process; we're each discovering new things everyday. Maybe, just maybe, we should share the details of the historical process with folks in our historic sites. Perhaps we have an obligation as public historians to help folks understand that 'historical revisionism' isn't necessarily a bad word.

|

A colorized version of the burning of the large and small arsenals as drawn by

David Hunter Strother from the collection at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park |