Frederick Eshelman's father wasn't home. He was in Petersburg, the chilly and treacherous trenches stretching to his right and left as far as the imagination might take them. That's where the danger was. That's where war lived.

And in Fairfield, Pennsylvania, the war was about as far away as it could be. Tides of battle had lapped at the borough and the county, men had trampled the streets and horses had broken into a gallop on the way toward the gap at Monterey Pass. But it was January now and the muddy roads were crispy and quiet.

Catherine Eshelman was now a single mother. Her husband Hiram was alive and well, but she had to raise her passel of children without his help, without his influence. Frederick was 7. His sister Sarah was a year older. His older brothers John and William were about 9 and 11. Though Catherine had Mary, her daughter of about 15, to rely on, keeping watch over so mane children in such a lonely house must have been tough.

Every house in Adams County had the weird and odd relics of war. Some places they were hunks of iron, pieces of shells lined along a mantle. Others had swords hung on walls, abandoned by officers long ago captured and imprisoned.

And some homes, like the Eshelman's, had even more awkward souvenirs of war: rusting and broken gun barrels.

One of Frederick's brothers, playing with the weapon-turned-toy, shoved the butt of the barrel into the coals of the wood stove. He grabbed his little brother and told the 7-year-old to listen to the tube.

The sounds of gunfire were old hat to Hiram Eshelman in the trenches at Petersburg. By 1865, most soldiers were no longer phased by rifles, cannon and explosions. Even his scant few months since September in the ranks likely had deadened Hiram's ears to that sound.

But Catherine, in peaceful Fairfield, heard that sound anew. She heard that jarring bang and that sickening splatter of what once was her beloved son's skull burst to pieces. On the 17th of January, 1865, a long forgotten bullet from the grand invasion of Pennsylvania finally found its mark in a 7-year-old boy's brain, another casualty of the battles near Gettysburg.

Hiram Eshelman marched home a few months later. War had taken from the family, but not in a way anyone might have expected.

Showing posts with label Casualties. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Casualties. Show all posts

Thursday, January 15, 2015

Wednesday, July 9, 2014

A Carriage Ride from Home

|

| The Georgetown Pike Bridge, near where the 87th Pennsylvania bathed in their own blood. / PD LOC |

Gathered around their table were his brothers and sister. David and Louisa were a few years older than the 19-year-old Elias. Robert and Jacob were his younger brothers, 16 and 14-years-old, who likely helped out around the shop when they weren't studying.

When the war began, Elias leapt to the call. Literally in war's first moments, immediately after Lincoln put out the call for volunteers, Elias signed his name on a form and marched to Harrisburg to join the troops who would end the rebellion swiftly and decisively.

In 90 days, he was discharged and America was shown this might not be a quick war.

So Elias joined the army again.

While he was gone, most of Elias father's market for carriages had likely dried up. Did the family need that money now? Was it helping make up for the cash that no longer flowed from wealthy, carriage-buying slaveholders in the Shenandoah Valley? Elias, to some extent, was helping to destroy his family's livelihood while he marched in the United States army. The slave wealth of the South paid for the fancy carriages he built in a previous lifetime.

By July of 1864, the 87th Pennsylvania had seen blood. And as rebels again charged toward the border, they were detailed from Petersburg's defenses to head toward Washington City and protect it from the oncoming tide of Early's raid on the Capital.

Gettysburg knew just moments after the fighting stopped that a battle had happened at Frederick, Maryland. But who was there? Were they dead?

Did Mary Sheads frantically search the columns of the Compiler on the 11th or the Adams Sentinel on the 12th, looking for Elias' name?

Or by now had he been gone so long, been threatened so many times in her imagination, that it was a mundane slow finger rolling down those columns? After seeing the suffering of last summer in her own streets, was her search now simply for the inevitable, not the dreaded? Was war normal by this its fourth long, hot summer?

In a field south of Frederick, Elias Sheads Jr. suffered the inevitable. The 87th was standing astride the Thomas Farm, Georgians charging headlong into their lines. A fragment of shell sailed through the air and buried itself into Elias' shins. Both his feet were shattered, blown to pieces, sheared clean off.

|

| Elias Sheads Jr.'s final trip home ended here. / Find-A-Grave |

He had worked wood with his father, driven pins and nails, laid down leaf springs and set axles. He had built the wagons which easily rolled between Gettysburg and Frederick before this cruel war. He used to make the world smaller, the distances shorter. He and his father transformed a few days' walk into a few hours' ride. If only he could make that ride, leap into a carriage and just go home.

But he couldn't. Instead, he lay, bloody stumps where his feet used to hold him up as he worked. Just a stone's throw from his father and mother, from David and Louisa and Robert. A stone's throw from safety at home.

His body made that one last trip his conscious mind never could. Elias Sheads Jr. was buried atop Cemetery Hill in Evergreen Cemetery.

As soft earth was moved in Gettysburg, somewhere in the trenches around Petersburg, Elias' little brother Jacob stood in the ranks. The 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry, lately transformed into infantry, was moving back and forth along the line, preparing for fight after fight. Jacob, who went by James, was nearly 18-years-old.

Another of Mary Sheads' boys was just waiting for the inevitable.

Labels:

1864,

Casualties,

Cemetery,

CW150,

Death,

Gettysburg,

Monocacy,

Rudy,

Sheads

Location:

Gettysburg, PA 17325, USA

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

One Year On: Preparing a Somber Holiday

|

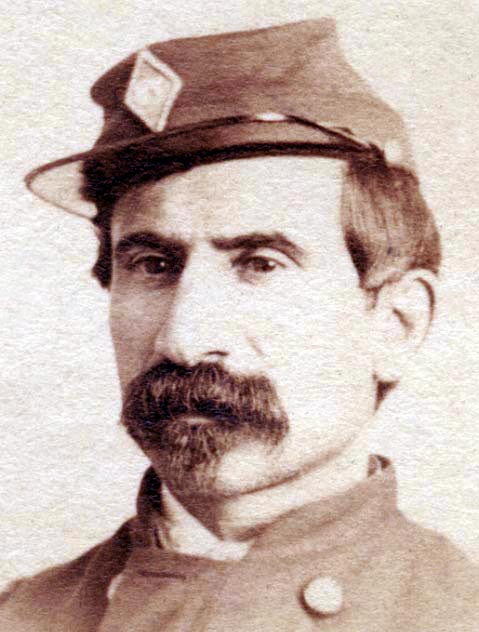

| Lieutenant Colonel James Alonzo Stahle, whose brother managed Gettysburg's fiercely Democratic Compiler, sometime before March 1864. |

But laying out the paper in those first few hot days in July must have been agony for reasons far beyond the raw labor. The words themselves were distressing.

In the neat columns of type sat a letter. Henry Stahle, the Gettysburg Compiler's editor had received it a few days before. Though it was signed simply, "Zoo-zoo," it was likely from Stahle's own brother, James.

Lieutenant Colonel James Alonzo Stahle fought with the 87th Pennsylvania. When war broke out in 1861, James Stahle organized a local milita unit, York's own version of the "Ellsworth Zouaves." By 1864, he had risen to the upper eschelons of the 87th, commanding men mostly from York and Adams County.

Zoo-zoo, that nom-de-plume of the prolific correspondent to the Gettysburg Compiler was an obvious nod to the flamboyant Zouaves. And Editor Henry J. Stahle reprinted the neatly set letters prolifically.

But dropping these letters into the frame, laying out these sorts, must have been harrowing for a loving brother. Zoo-zoo's letter in the July 4th edition was full of such palpable grief.

"The last rays of the sun are still glimmering up the evening sky," Zoo-zoo wrote, "faintly throwing their fading light upon the tall pines that skirt the borders of these swamps, whose dirty, sluggish waters find an outlet in the ever memorable Chickahominy." The cratered moonscape of Cold Harbor stretched before his eyes. "Looking toward the west, and strong strong earth-works, trenches and bomb proofs are all that meet the eye," he wrote. But turn around and the landscape changed. It was scattered with graves, the final resting places of, "many who yesterday were among the busy thousands that were battling for their common country."

Zoo-zoo knew that mothers across America, in Ohio and Pennsylvania, New York and Vermont were mourning. And he was mourning too.

"Among the hundreds of little boards that mark the simple graves, my eye rests on one that calls back to memory the face of one who but a few days ago was among us, in the full enjoyment of vigorous health and strength." That tiny board read, "Isaac Sheads."

Sheads joined Stahle's 87th Pennsylvania in September of 1861, after it was obvious this spat might last for not months but years. But most of the 87th's war was in garrison duty in Western Virginia, dancing around Harpers Ferry and Winchester for the better part of two years. It wasn't until 1864 that they began seeing war's cruelty in spades.

Sheads survived the raging fires of the Wilderness. Sheads watched as the other regiments from his Corps charged forward under Emory Upton in an awkward and new formation, forever changing warfare at Spotsylvania. War was becoming very real and very raw as 1864 crept on.

Then, at Cold Harbor, Isaac Sheads' war ended.

"Isaac Sheads was but an acquaintance of few years' standing," Zoo-zoo wrote to his brother the newspaper editor, "yet in this time he so endeared himself to many of us that an unbidden tear will spring up from the heart at the thought that he is no more with us." As Stahle and his pressmen transcribed the letter into lead type did they need to decipher ink through tear stains on that sheet of paper? What had this private, this invisible man in the ranks, done to endear himself to an entire regiment, to its Lieutenant Colonel?

|

| Isaac Sheads avoided the fate of many from the Cold Harbor battlefield. He has a named grave, and was eventually reinterred in Gettysburg's Evergreen Cemetery. / PD LOC |

Henry Stahle needed to keep going, needed to build this week's paper. But his brother's words must have at least given him pause, made him yearn to comfort his flesh and blood. It would have made any man's brother pause.

"Birds will warble their sweet matin songs," Zoo-zoo imagined amid the din of battle, "over no braver man than Isaac Sheads." Even in a blasted hellscape like Cold Harbor, as the final shots of a battle found their mark, a soldier's eyes could imagine a new dawn through bitter tears.

And as all of Gettysburg unfolded their newspapers on the glorious Fourth of July in 1864, everyone saw those tears and knew the costs of this cruel war.

The Fourth might be a memory of victory from last year, but war still raged on just shy of two hundred miles south to disastrous and heartrending ends one year on.

Labels:

1864,

Casualties,

Cold Harbor,

CW150,

Death,

Letter,

Newspapers,

Rudy,

Stahle

Location:

Gettysburg, PA 17325, USA

Tuesday, June 3, 2014

Gettysburg's Tragedy in Virginia

|

| The 138th's VI Corps fighting through the Wilderness |

The two boys were the youngest members of their family. When the war erupted, their mother and father, Samuel and Jane, lived alongside their daughter Catharine. Jacob was an apprentice blacksmith in B.G. Holabaugh's shop. John still lived at home with his parents.

August of 1862, the brothers joined the army alongside dozens of other men from Adams County. Company B of the 138th was chock full of names which still bedeck Adams County's mailboxes and backroads.

But while battle raged at home in July of 1863, while rebel bullets threatened mother, father and sister, the Kitzmiller boys found themselves guarding quartermaster stores en route to Washington alongside the Potomac. While men proved their mettle in the streets where the Kitzmillers grew up, they were guarding crates of hardtack and shelter halves.

But the two brothers eventually found the war. The 138th Pennsylvania bounced around the Army of the Potomac, finally landing in the 6th Corps in time for the battle in the Wilderness in 1864.

The men from Adams County charged through a tight bramble just north of Saunder's Field, while the forest roiled with smoke and fire in the chaotic battle. And somewhere in the fray, the two Kitzmillers stood in line of battle.

Were Jacob and John near each other? Did they stand shoulder to shoulder, to brothers on an adventure. The blacksmith Jacob and his little brother John were somewhere in that hellish scene, the scent of brimstone from charred gunpowder curling through their nostrils.

Then Jacob felt a sharp pain in his strong left arm. That muscle which had steadied hot iron against an anvil, learning the trade of the noble blacksmith, dangled limp and shattered. Tragedy had struck.

Jacob lost his arm after being dragged to a field hospital. His war was over. But so was his life as he had imagined it.

And John fought on alongside the Bieseckers and McCrearys and Deardorffs. His brother was no longer there. Was it harder? Where did he find the strength to keep on marching forward? War had stolen his brother's arm. And here John stood, still on the front line.

He didn't have to fear for long.

Almost as an afterthought, in the Compiler in the first few weeks of June, the notice ran. "A letter just received from Lieut. Earnshaw, of Co. B, 138th Reg., states the casualties in the company as follows: - Killed, John Kitzmiller."

Just two years earlier, Kitzmiller's death might have warranted a full column of text, a eulogy for a young man destroyed in his prime. It might have called for fanfare, for pomp and circumstance. But reality had struck Gettysburg with a vengeance. For a town which had witnessed the deaths of 10,000 men, who had watched as three times that many others limped or rolled through their streets, what was one more lifeless form to be added to the grotesque pile?

But the two boys weren't just lifeless forms. They were a son shattered and a son killed. For the Kitzmiller family in Gettysburg, 1863 may have been tough. But 1864 was an absolute tragedy. One insignificant name in a newspaper, hearing your son has lost his left arm, is enough to shatter a mother's heart, leave a father crippled with grief. Worrying over that young man, now missing his trade and writhing in pain in a Washington City hospital must be sheer agony for a mother. And agony becomes inconsolable when a second name, dropped nonchalantly by a typesetter in a newspaper office on Baltimore Street, reaches the Kitzmillers' eyes.

Gettysburg might have been deadened to tragedy, but that didn't stop tragedy from squeezing its way through the tough exterior to shatter heart after heart in 1864.

Labels:

Casualties,

Cold Harbor,

Death,

Newspapers,

Not Trivializing Death,

Rudy,

Wilderness

Location:

Gettysburg, PA 17325, USA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)