|

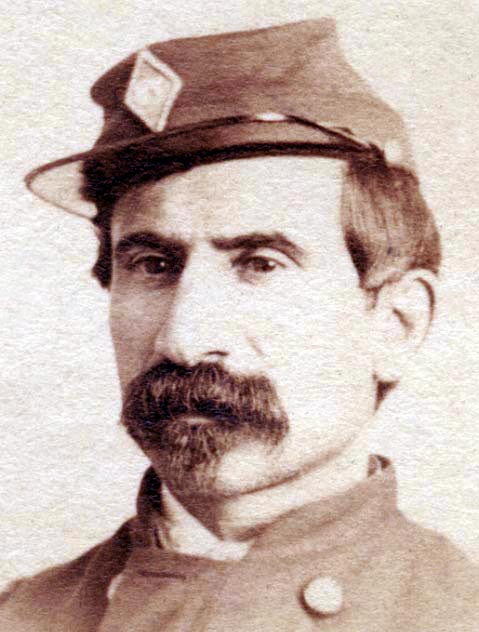

| Lieutenant Colonel James Alonzo Stahle, whose brother managed Gettysburg's fiercely Democratic Compiler, sometime before March 1864. |

But laying out the paper in those first few hot days in July must have been agony for reasons far beyond the raw labor. The words themselves were distressing.

In the neat columns of type sat a letter. Henry Stahle, the Gettysburg Compiler's editor had received it a few days before. Though it was signed simply, "Zoo-zoo," it was likely from Stahle's own brother, James.

Lieutenant Colonel James Alonzo Stahle fought with the 87th Pennsylvania. When war broke out in 1861, James Stahle organized a local milita unit, York's own version of the "Ellsworth Zouaves." By 1864, he had risen to the upper eschelons of the 87th, commanding men mostly from York and Adams County.

Zoo-zoo, that nom-de-plume of the prolific correspondent to the Gettysburg Compiler was an obvious nod to the flamboyant Zouaves. And Editor Henry J. Stahle reprinted the neatly set letters prolifically.

But dropping these letters into the frame, laying out these sorts, must have been harrowing for a loving brother. Zoo-zoo's letter in the July 4th edition was full of such palpable grief.

"The last rays of the sun are still glimmering up the evening sky," Zoo-zoo wrote, "faintly throwing their fading light upon the tall pines that skirt the borders of these swamps, whose dirty, sluggish waters find an outlet in the ever memorable Chickahominy." The cratered moonscape of Cold Harbor stretched before his eyes. "Looking toward the west, and strong strong earth-works, trenches and bomb proofs are all that meet the eye," he wrote. But turn around and the landscape changed. It was scattered with graves, the final resting places of, "many who yesterday were among the busy thousands that were battling for their common country."

Zoo-zoo knew that mothers across America, in Ohio and Pennsylvania, New York and Vermont were mourning. And he was mourning too.

"Among the hundreds of little boards that mark the simple graves, my eye rests on one that calls back to memory the face of one who but a few days ago was among us, in the full enjoyment of vigorous health and strength." That tiny board read, "Isaac Sheads."

Sheads joined Stahle's 87th Pennsylvania in September of 1861, after it was obvious this spat might last for not months but years. But most of the 87th's war was in garrison duty in Western Virginia, dancing around Harpers Ferry and Winchester for the better part of two years. It wasn't until 1864 that they began seeing war's cruelty in spades.

Sheads survived the raging fires of the Wilderness. Sheads watched as the other regiments from his Corps charged forward under Emory Upton in an awkward and new formation, forever changing warfare at Spotsylvania. War was becoming very real and very raw as 1864 crept on.

Then, at Cold Harbor, Isaac Sheads' war ended.

"Isaac Sheads was but an acquaintance of few years' standing," Zoo-zoo wrote to his brother the newspaper editor, "yet in this time he so endeared himself to many of us that an unbidden tear will spring up from the heart at the thought that he is no more with us." As Stahle and his pressmen transcribed the letter into lead type did they need to decipher ink through tear stains on that sheet of paper? What had this private, this invisible man in the ranks, done to endear himself to an entire regiment, to its Lieutenant Colonel?

|

| Isaac Sheads avoided the fate of many from the Cold Harbor battlefield. He has a named grave, and was eventually reinterred in Gettysburg's Evergreen Cemetery. / PD LOC |

Henry Stahle needed to keep going, needed to build this week's paper. But his brother's words must have at least given him pause, made him yearn to comfort his flesh and blood. It would have made any man's brother pause.

"Birds will warble their sweet matin songs," Zoo-zoo imagined amid the din of battle, "over no braver man than Isaac Sheads." Even in a blasted hellscape like Cold Harbor, as the final shots of a battle found their mark, a soldier's eyes could imagine a new dawn through bitter tears.

And as all of Gettysburg unfolded their newspapers on the glorious Fourth of July in 1864, everyone saw those tears and knew the costs of this cruel war.

The Fourth might be a memory of victory from last year, but war still raged on just shy of two hundred miles south to disastrous and heartrending ends one year on.