"...today I want to say to the people of America and the nations of the world, that we are not about to turn around. We are on the move now. Yes, we are on the move and no wave of racism can stop us. We are on the move now."

The last time I went to a Catholic Mass was on Easter last year. My head was in a bad place. I felt all alone. Mom was gone. and the landscape of the world looked entirely foreign. Even the Mass itself had changed. New responses replaced old ingrained phrases. My mouth didn't match the rest of the congregation. I was lost.

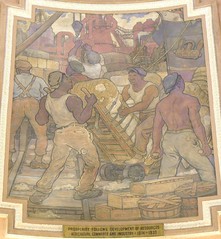

This morning, I stood with a group of people of whom I am eminently proud. What we've done in the past few days is fundamentally different than any other interpretive program undertaken by the National Park Service. Period. Full Stop.

We have embarked on a radical new form of interpretation, discovered almost accidentally. It's something I might call democratic interpretation if I was even so presumptuous as to name it. I'm not sure it can be named by any one person. There is no interpreter, there is no audience. There is only We. The playing field is leveled.

We are a community learning from one another. We respect each other but are frank enough to ask tough questions honestly and openly. And the answers we share are at once profound and simple. There is no way any of us will forget this week's events.

In some way, this week hasn't been about the march from Selma to Montgomery as much as it has been about being human. We've been recreating a march, but that quickly evaporated as a goal. This week has been about people making real, lasting, meaningful connections with one another, understanding each other in a visceral way that's hard to categorize.

I will never forget the long talk about popcorn and rice that Aja and I shared as she unknowingly helped me keep my mind occupied through a painful mile or two. Or exploding fist-bumps with Hanif, or the fact he realized being a historian means you can study all of history, ricocheting from decade to decade and not just focusing on some boring myopic corner of the past. He left for home too soon in the march for me to ask what the Arabic writing on his arm said. I'll never forget hearing how gay folks aren't really as bad off as I thought in South Carolina. I'll never forget hearing about how you can fight for social justice on the clock, then go right back to doing it when you get back home at the end of the day. I'll never forget shaking hands and hugging and laughing. I'll never forget we have lived as a truly caring community these past few days.

I won't forget the causes I've seen dangling from placards on backpacks and plastered across protest signs in crayon and glitter either. "I march for Education." "Women's Rights are Human Rights." "I march for Change." "I walk because this is the 'America' I believe in."

But mostly I won't forget the simple fact that I am not alone. Today we crossed into the City of Montgomery. None of us ever could have achieved the momentous feat alone. We are not individuals; we are a true "We."

Sitting in the sanctuary at the City of Saint Jude tonight, swaying to the tune of "Lift Every Voice and Sing," I realized it was the first time I've been in a Catholic Mass since two days before my Mom's funeral. I also realized I would never be truly alone in this world - even when I'm hundreds of miles from the people I love. If I just put in the effort, I can have every single human beside me as a friend. All I need do is stop to strike up a conversation.

And I knew that for the last three miles on the long trek to the capitol tomorrow I would be with my family.

All 300 of us.