A broad sweeping portico looms behind the gay couple riding horses on a summer's afternoon. The man wears a brown coat and tall black top hat. The woman dresses in the finery of the turn-of-the-century. A hunting dog stands at attention as the horses stride across the plantation's spacious lawn. Back on the porch, a black "mammy" figure watches over a young girl.

The scene is one of eight which adorns the dome of Alabama's State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama. The mural, titled, "Wealth and Leisure Produce the Golden Period of Antebellum Life in Alabama, 1840-1860," is the work of

Roderick MacKenzie, a London-born artist and adopted son of the Cotton State. MacKenzie was born in 1865, his family emigrating to Mobile, Alabama at the tail end of the reconstruction period. After his mothers' death, his father broke the family up, sending the fifteen year old Roderick to an orphanage, run by the Episcopal Church. The young man took to art, developing an eye for industrial scenes of slag pits and foundries.

In 1926, MacKenzie was chosen to paint the eight murals which adorn the Alabama Capitol's dome. Among the scenes are Hernando de Soto meeting with Chief Tuscaloosa, the British surrender to Jackson in 1814 and the drafting of the state's first constitution at Huntsville.

But the most interesting set of images are the final three in MacKenzie's series. I noticed the odd grouping when I visited Montgomery this past August, taking refuge in the Capitol during a late summer thunderstorm. The three images, taken as a group, struck me as oddly symbolic.

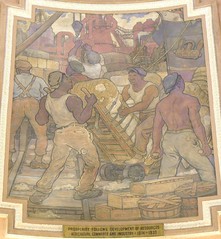

First is the aforementioned, "Wealth and Leisure Produce the Golden Period of Antebellum Life in Alabama, 1840-1860." Next, comes, "Secession and the Confederacy, Inauguration of President Jefferson Davis, 1861." Finally, rounding out the dome and sitting jarringly beside both Davis and de Soto is, "Prosperity Follows the Development of Resources Agriculture, Commerce and Industry, 1874-1930."

The three murals span nearly a century of American and Alabamian history. MacKenzie painted the images in the heart of the Civil War's memory period, as reunions for the 75th anniversary of the war's battles were coalescing. But MacKenzie also crafted the images in the heart of what Rayford Logan and James Loewen call the nadir of American race relations. The paintings stand as brilliant encapsulations of the view of the antebellum, bellum and postbellum landscape as seen from the American South in the 1920s.

Jefferson Davis stands as a signpost between the two stages of the South, leisure and work. The war years are represented by that hopeful moment when Jefferson Davis took an Oath of Office to a nation not yet won, on the steps outside the building. No bloody struggle, no military defeat or victory is depicted, just a hopeful tableau of Davis, the only President of the Confederacy.

The leisure of the first image of the series, that of, "the Golden Period of Antebellum Life," gives way to a bustling scene of dock workers loading baled cotton onto ships. But the image on Davis' left hand of dock workers is eerily much like that on Davis' right of plantation leisure. The workers on the dock, although strong and powerful, are subjugated black men depicted with low clothing and deep grins on their faces. The men resemble caricatures of blacks from American minstrelsy and it's decedents, with the broad toothy grins of the, "happy darky." The dock worker hoisting a dolly particularly, is contorted in a manner which struck me instantly as akin to Stepin Fetchit, the stereotypical character played by black actor Lincoln Perry beginning in 1925.

But the scene of leisure from the antebellum period had a similar scene buried behind its layers of paint and canvas. When I looked at the scene of the "big house" and the couple out for a Sunday jaunt on horseback, I saw what lay behind the house. Slaves, toiling in cotton fields and over stoves. I saw them feeding horses fodder in the stables, shoveling the shit away to clean the barns for mistress' dainty feet as she walked to her mount for that stroll, the tawny men and women themselves dying in filth and stink under the hand of oppression.

The dock workers, likewise, shouted "oppression" at me as I stood in the rotunda. The smiles, which MacKenzie manufactured for them, hid the disdain of loading cotton, staple of the insidious sharecropping system which helped the institution of slavery live on in modified form for nearly a century after the guns of freedom ceased. The only labor in the image is black, lower class. Missing from the image are white laborers. The message was clear to me: they're still subjugated, still a lower class of being. Somewhere behind those ships and those workers was a couple still riding their horses, leisure on the backs of oppression and inequity.

But missing too from the image were Benjamin Turner and Jeremiah Haralson, both former slaves who served as United States Congressmen for Alabama in the post-war period. They were certainly no man's property. Missing too was adopted Alabamian Booker T. Washington, himself a former slave who served as the first President of Alabama's nearby Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. In the late 1920s, during the nadir of race relations and the violence of the second Klan's reign in America, MacKenzie depicted the neo-slave of Alabama, still toiling at the feet of the President of the slave nation, Jefferson Davis.

It may seem like I could be jumping to a lot of conclusions in my analysis. I could be. But below those 1920s murals, on the lower level of the rotunda, hangs an equally jarring portrait. George Wallace, governor of Alabama from 1963-1987 (intermittently), stands defiantly on one wall, a giant smile on his face. On his desk sits a Bible and small statue of liberty. Behind his right shoulder hangs an American flag. Behind his left, nearest his head, hangs the Confederate. The man once called Alabama the, "very Heart of the Great Anglo-Saxon Southland," and declared that he would, "draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny... and I say... segregation today... segregation tomorrow... segregation forever." Here he stands, immortalized in oil and hanging on the wall. He hangs along with MacKenzie's murals, the pitch perfect image of his dream of the American South.

Before I left the deserted Rotunda on that rain soaked afternoon, I quietly held up my middle finger at Wallace's grin and stood there transfixed for a moment. I felt invigorated at my act, like I had just stood in a schoolhouse door and was off to conquer the world.

I shudder now. That's a frightening feeling.