Hot off the YouTubes... Just found this on the perennial font of good, bad and weird. In this case, I'm thinking it's along the lines of excellent:

OK, so what are we looking at? First and foremost, we are looking at someone who has thought deeply about the meaning of Lincoln's words at Gettysburg. "President Lincoln changed history / he honored the dead but did so much more / he changed the meaning of the Civil War." MC Lala gets the deep meanings of the two minutes Lincoln spent on a platform in Gettysburg. MC Lala grasps the deep importance of Lincoln's re-dedication of America at Gettysburg using the Declaration of Independence's ever inspiring promise that, "all men are created equal."

And here's where this gets interesting: the good MC is sharing that meaning quite adeptly. It's not hard with the Gettysburg Address itself. Lincoln at Gettysburg was being an interpreter himself, attaching new meanings of freedom for all to the tangible resource that was the blood soaked ground under the audience's feet.

But MC Lala encapsulates the meaning of the speech in a consumable form which sticks in the modern mind. Almost every bit of Lincoln's intended meaning is there.

I've watched some of MC Lala's other work (under the username "dilalpe") and have been enamored with it. I don't think the songs and videos simply speak to youth or a hip-hop generation. I think they can speak to any of us. Historical meanings which resonate universally: isn't that what we want and need as a society from the Civil War?

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Thursday, September 15, 2011

In Another Sesquicentennial

On Tuesday, Jake wrote asking who controls the memory of 9/11. The ownership of memory is such an interesting thing. This tenth anniversary was an interesting event, fraught with conflicted memory and different voices. It was intriguing to watch all of the slight conflicts which emerged last week leading up to the ceremonies on Sunday morning.

It has also been interesting to see the Civil War analogies to which a few folks, particularly John Hennessy and Kevin Levin, have pointed, viewing Civil War memory as an interesting case study of how 9/11 might be commemorated and memorialized in coming decades and centuries.

Coincidentally, I have been picking away for a few weeks now on a small thought experiment, inspired by the hot morning I spent at Manassas in July. What could the sesquicentennial of an event like 9/11, an event we have collectively sworn to "never forget," look like? Envision it as a simple piece of science fiction, like reaching forward through a hole in time 150 years and plucking out a news story on the anniversary commemoration of the attack on the Pentagon. And like all Science Fiction, it is more about the events of the present than the events of the future.

As Rod Serling, master of Science Fiction said in his introduction to the Twilight Zone episode "In Praise of Pip":

"Submitted for your approval..."

It has also been interesting to see the Civil War analogies to which a few folks, particularly John Hennessy and Kevin Levin, have pointed, viewing Civil War memory as an interesting case study of how 9/11 might be commemorated and memorialized in coming decades and centuries.

Coincidentally, I have been picking away for a few weeks now on a small thought experiment, inspired by the hot morning I spent at Manassas in July. What could the sesquicentennial of an event like 9/11, an event we have collectively sworn to "never forget," look like? Envision it as a simple piece of science fiction, like reaching forward through a hole in time 150 years and plucking out a news story on the anniversary commemoration of the attack on the Pentagon. And like all Science Fiction, it is more about the events of the present than the events of the future.

As Rod Serling, master of Science Fiction said in his introduction to the Twilight Zone episode "In Praise of Pip":

"Submitted for your approval..."

"The Defining Moment of Modern America"

Attack Anniversary Commemorations Draw Modest Crowds

Thomas Farquad for the Washington Post, Sunday, September 12, 2151

A crowd of about 650 people gathered at the west wall of the old Pentagon on Saturday morning to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the attack of September 11th, 2001. Dignitaries from District government, as well as the Commonwealth of Virginia were present.

"The men and women who fought the fires in these old walls on that day in September were brave, honest and hard working Americans," Virginia Governor Chauncey Williamson told the crowd. The Pentagon was in Virginia in 2001 when the attacks took place. The District of Columbia Statehood Act of 2076 transferred the land back to District control.

"The attack that happened here sent a shock wave through the world," the Governor remarked, "For two decades, wars were fought over the question of what our nation’s role in the world should be." Governor Chauncey said the unity seen in the years after the attack was a "blessing born from the heart of a tragedy."

District of Columbia Governor Samuel Williams, whose great-great grandfather was mayor of the city when the attacks took place in 2001, said that, "the lessons of so long ago are still relevant today." Quoting President Malia Obama, Williams reminded the crowd that, "America is fundamentally a good nation, with good intentions, good people and good morals. But we drift outside of our boundaries sometimes and need to stop to re investigate who we are."

Carter Smithson said he came to the Pentagon to honor his ancestor who died when the plane hit the building in 2001. Smithson, a clerk at the State Department, was dressed in the uniform of a 20th century army officer. "I represent my great-great-great grandfather today. These are the same types of clothes he wore when he died that day."

Smithson saw the small crowd as discouraging. "I wish more people had come out to commemorate both the awful tragedy and the unity that came out of it." Smithson sees America as a "stronger nation, more united" in the wake of 9/11.

On the opposite side of the park, Gerald Willson talked to the public about those who boarded the planes and fought for their freedom. "They were protecting their way of life," Willson told the crowd. "They were fighting for a cause they thought just."

Willson, an investment banker from Rockville, MD wore a headscarf and carried the chosen tool of the Islamic fighters on board the aeroplanes, a small knife called a "box cutter."

"I do this to make sure that the story gets told," Willson said. "Liberal historians want to focus so much on the causes of the war. They say these men were fighting to destroy America." But Willson feels the men were fighting, "in a revolution to ensure that their nations weren't tampered with." Willson said we need to, "remember the bravery of the people who fought on both sides on nine-eleven."

Anne Gerald, a systems analyst from Arlington saw the event differently. "Today is about the Americans who died here," she commented. "The men on the planes were not freedom fighters like some want to portray them, but simple murderers."

The park along the west wall of the Old Pentagon Commercial Park is open daily, sunrise to sunset and accessible from Pentagon Metro station.

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Holy Writ: Thinking Beyond Enabling Legislation to Modern Relevance

Just a quick one today...

Why trust a bunch of dead guys? I know it sounds trite, but it's very important when we begin approaching how we talk about Civil War sites (or any historic site). Oftentimes, the folks who voted the site into existence and decided its primary reason for being are dead and gone. The world has changed radically since they were here. The pieces of legislation they created (at the federal level they're typically called "enabling legislation," at lower levels they have varied other names) were distinct products of their times. The themes and significances they outline are likewise products of their times.

Take the first military parks for example, founded in the 1890s as a place for the War Department to simply preserve and explain the battle lines of the Federal and Confederate armies. America needed unity in the wake of war (we needed unity so desperately, we went to war again just a few years later with Spain and in the Philippines). Discussing the battle tactics and battle lines, focusing on shared valor, ensured that this unity could be forged. But does this land mean the same thing 100 years later, after successive civil rights movements, social upheavals, political realignments and military conflicts which have altered the American views of war?

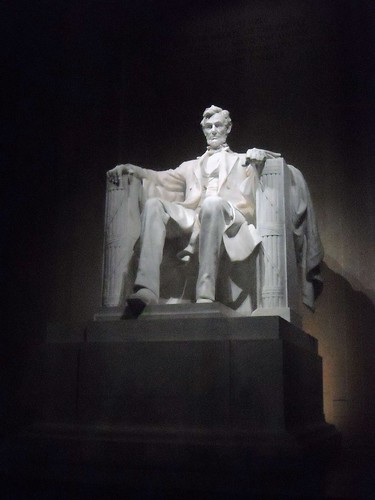

|

| I took this photo the morning of the 2009 inauguration. Did the meaning of this simple piece of marble shift somehow that day? |

What are these historic sites and battlefields all about? To me, it has to be about helping visitors find their own personal meaning for the ground beneath their feet. This means that there are no correct resource meanings, only personal resource meanings. My personal meanings for a site are never the only ones I should offer to visitors. A dictatorship of meaning, imposing my views on a visitor, is just as bad as a visitor finding no meanings for a site. In the end, interpretation fails when the visitor is not provoked to think about meaning.

In the end, enabling legislation is not sacrosanct. Only the Visitor is Sovereign. The meanings they find for our battlefields are the only ones that matter. It's about how a modern audience finds these places useful and meaningful. Anything else doesn't really matter.

Thursday, September 1, 2011

"And preachin' from my chair": The Historian and the Interpreter

I've been thinking lately of titles. The new blog Emerging Civil War's inaugural post touched off a powder-keg of thought for me. Looking down the list of contributors yields name after name listed as "historian at...." But most of those folks appear to have the official job title of "park ranger," "interpreter," or "visitor use assistant," and not "historian." This got the wheels in my head turning.

What we choose to call ourselves is sometimes as important as the work we do. For those who 'do history' on Civil War battlefields, we have two distinct options. The best place to find how someone views themselves is right in their e-mail signature, but sometimes it's in the bio they put on their blog.

Some fashion themselves as historians first and foremost, imparting the historical truth to their audience. They persuade and argue a thesis for their audiences, acting as the professor in walking lectures with distinct points to prove.

Others see themselves as interpreters first and foremost, offering opportunities for visitors to connect with a site's meanings, to find meanings that the member of the audience find personally relevant. They offer multiple perspectives and a variety of viewpoints, acting as a facilitator, orchestrating a conversation between the resource and the visitor with no thesis to argue.

Historians persuade; Interpreters reveal.

There is nothing inherently wrong with persuasive argument. But often historians on battle landscapes craft grand arguments with very specific theses. The historians dictate the conclusions and demand acquiescence to those conclusion by laying out every point of their argument to support their theses. They argue a point. There is what could be called a dictatorship of thought.

On the flip side of that coin, interpreters leave conclusions to their audience, offering multiple perspectives on an event and moral ambiguity. No one ends up having been right or wrong. This past summer, I've been running discussion-based experimental programs on John Brown. In the end, when the visitors step out of the engine house, I don't care what they think about John Brown. Some walk out loving him, thinking him a saint. Others walk out thinking him a terrorist and the devil incarnate. There is no right and wrong conclusion, only the visitor's conclusion. If they walk out thinking something, anything about John Brown, I've done my job. Think of it as a democracy of historical thought.

Take a look at the top of the blog. Go on... scroll up there. I'll wait. There's a very distinct reason we chose that title. "Interpreting the Civil War."

Yes, we'll argue historical points vehemently here in our own backyard, because to some extent we're hashing out our own personal meanings of these places. You have to care about something personally before you can help others find why they care about it too. But when we head out into the sacred spaces that America has set aside for itself, there is no right and wrong. There is muddy chaos, moral ambiguity and the visitor's conclusion. There are no theses. There are no right answers or acceptable opinions.

There is only the visitor and their personal appreciations of the places we hold dear.

|

| What does it all mean? Who am I to say? |

Some fashion themselves as historians first and foremost, imparting the historical truth to their audience. They persuade and argue a thesis for their audiences, acting as the professor in walking lectures with distinct points to prove.

Others see themselves as interpreters first and foremost, offering opportunities for visitors to connect with a site's meanings, to find meanings that the member of the audience find personally relevant. They offer multiple perspectives and a variety of viewpoints, acting as a facilitator, orchestrating a conversation between the resource and the visitor with no thesis to argue.

|

| A historian emeritus from Princeton on a battlefield... |

There is nothing inherently wrong with persuasive argument. But often historians on battle landscapes craft grand arguments with very specific theses. The historians dictate the conclusions and demand acquiescence to those conclusion by laying out every point of their argument to support their theses. They argue a point. There is what could be called a dictatorship of thought.

On the flip side of that coin, interpreters leave conclusions to their audience, offering multiple perspectives on an event and moral ambiguity. No one ends up having been right or wrong. This past summer, I've been running discussion-based experimental programs on John Brown. In the end, when the visitors step out of the engine house, I don't care what they think about John Brown. Some walk out loving him, thinking him a saint. Others walk out thinking him a terrorist and the devil incarnate. There is no right and wrong conclusion, only the visitor's conclusion. If they walk out thinking something, anything about John Brown, I've done my job. Think of it as a democracy of historical thought.

Take a look at the top of the blog. Go on... scroll up there. I'll wait. There's a very distinct reason we chose that title. "Interpreting the Civil War."

Yes, we'll argue historical points vehemently here in our own backyard, because to some extent we're hashing out our own personal meanings of these places. You have to care about something personally before you can help others find why they care about it too. But when we head out into the sacred spaces that America has set aside for itself, there is no right and wrong. There is muddy chaos, moral ambiguity and the visitor's conclusion. There are no theses. There are no right answers or acceptable opinions.

There is only the visitor and their personal appreciations of the places we hold dear.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)